PART 2: How to Start Exercising

Surviving The Chair - Part 2

This is the second part (or, as I prefer to call it, the practical follow-up) of my web-book, "Surviving the Chair: A Practical Guide to Restoring and Maintaining a Healthy Body for Those Who Sit a Lot."

Part 2 shows how to put the fundamental concepts introduced in the first half of the book into practice.

I intentionally kept this part separate from the rest of the book, because I wanted it to be an immediate entry point for those eager to start with fragmented exercising right away, even if they don't currently have time to read the whole thing. I understand! We are all busy people. That being said, I also believe that being busy should not hold us back from staying healthy, fit, and well.

Read on, try things out. If, at some point, you find yourself lost or confused by the terminology, find out more about the subject at hand by following the many links I’ve provided for you along the way.

Now you should be good to go, even if you skipped the first part. (Although, I do recommend that you read it eventually. Or better yet, read it as soon as you can. Just read it!)

A Brief Recap

Initially, this publication started out as an article covering a few essential tips for people new to exercising. As time has passed, I've extended and modified it countless times. The page grew in length, snowballing into a massive amount of information, excessively immense for a single web page.

Eventually, I decided to break it up into more digestible chunks. Presently, you are reading the transformed version of the article, which organically evolved into a full-fledged, comprehensive e-book on the subject of Fragmented Exercising.

I will refrain from a lengthy introduction. After all, that’s what the first half of the book was for. Here, I will just briefly recap the most essential and significant things we’ve discussed so far, as well as how they are the foundation for what’s to follow.

Attention: Before you start applying/using any information contained hereafter, please refer to the disclaimer and the terms and conditions for this website.

The Not-so-flat Approach

You might have already started connecting the dots. Or, perhaps, you’ve been waiting in anticipation to tackle this task along with the book. What I hope you have begun to notice and appreciate, however, is the fact that the described approach – fragmented exercising – can’t be compared to other wellness regimens or workout programs. Rather than forcing a person to narrow-mindedly concentrate on a set of exercises to perform a couple of times a week, we’ve discovered quite a few important game-changing variables at play; these variables add another dimension to the otherwise “flat,” oversimplified, and conventional approach to personal fitness.

Just like the “calories in, calories out” approach to dieting fails to address the complex issues associated with proper body nourishment, so do most exercise routines, diminishing the matter with a “do whatever you want as long as you stay active” attitude.

You see, just saying “eat less” or “move more” won’t suffice. Similar to how improper eating can cause many health issues through malnutrition, improper exercising can have a negative impact, as well. Wasting time on inefficient and ineffective solutions is one thing, but risking your health along the way is a bit troubling. And, yet, most of us do waste our own time and, unfortunately, harm our own bodies and our health by following baseless and outdated recommendations.

You might ask the question, “Do you mean to say that exercising can be harmful?” The answer? Yes!

Good Moves, Bad Moves

We’ve learned to differentiate “good foods” and “bad foods,” yet, we can’t wrap our heads around the idea of “good moves” and “bad moves.” Let’s look at this from another perspective.

Let’s say you live during a period of global famine. Or, better yet, imagine being a character in the series The Walking Dead. Can you see yourself scavenging through the ruins of supermarkets for remnants of food from the old world? Is there any type of food that you wouldn’t take? Would there be any food that you would call “bad food” in this situation? Can’t think of anything, right? Even a jar of mayo would seem like a lucky – or even life-saving – find.

That is because, when “no food” means certain death, any food becomes “good food.” To the same effect, when our sedentary society is starved of movement, any movement looks good. Does this approach, however, really help us to express ourselves optimally? Will we thrive, or will we just survive? Will it work for us in the long term?

Sidenote: You will often see me comparing exercising (or even just movement) to food. I can’t really tell you where I first came across this idea. Perhaps, it was one of Todd Hardgrove’s books; in his work, he often brings up the concept of a “balanced movement diet.” Anyways, I’m not claiming to be the first person to draw this connection. I’ll just admit that I find the comparison to be quite elegant and practical, helping to direct our attention to the integral importance of perpetual movement in our lives. Just as food is important for our survival, so is movement. I guess you can consider exercise to be another essential nutrient, without which your body can’t properly develop or thrive.

For over 25 years, we have been following the official recommendations promoted by the US Department of Health and Human Services and other authorities we’ve come to trust. We have adopted the unfounded daily goal of taking 10,000 steps*, which we think will “get us off the hook,” so to speak. In this time, we have seen increasing awareness among the general population in regards to the detrimental effects of inactivity; we have measured the growing trend of people exercising regularly. Even so, there has been no downturn in the prevalence of modern diseases.

(Read “Failed Recommendations”)

We can no longer accuse the general public of lacking self control and not being able to adhere to the official recommendations – in other words, for being lazy. Apparently, many of us do exercise. As a matter of fact, we exercise a lot more than we did at the time the recommendations were first published. It looks like the problem, then, is reflected in outdated conventions and the money-driven fitness industry, who serves us whatever is easier to sell.

Oh, you want a solution easy to fit into your busy schedule? Here you go: High-Intensity Interval Training (or HIIT) – the “best” thing in the world! Who cares if this type of exercise regimen comes with a great risk of injury, especially in the knees and shoulders, and especially among de-conditioned professional sitters?

I get it! You want something fun, so let’s do exercises based on martial arts or on dances. Why not!? Whatever makes you happy. We ask and they provide. Can we really blame the fitness industry for treating us like babies?

“At least we're active!” It’s better than nothing! Right? Wrong? How would we know?

Know Thyself

I believe that the only way to understand something better is to actually educate yourself on the subject. If you want to know the best way to take care of yourself and your health, spend some time learning about how your body operates. Try to understand the problems faced by us as a sedentary nation, or by you personally. Remember, we are all unique; don’t expect somebody to give you exactly what you need. They simply don’t know you that well – but you do!

Just like with food, we don’t automatically expect every single item sold at a grocery store to be good for us. It’s left up to the consumer to make that choice. That’s why we always read labels – if you don’t, you should – and that’s why there are strict food labeling regulations. Food producers often try to make the descriptions of their products sound better than they really are.

Similarly, there is a plethora of fitness solutions and approaches available to us these days. Their creators and the communities of avid proponents often go overboard in boasting about the benefits of these programs. You have to be able to tell what’s real and what’s not so that you can make an informed decision. Otherwise, you may end up wasting your valuable time, not getting the results you want, and, perhaps, even harming yourself.

That’s why you need to understand why you shouldn’t just do what a founder of a certain fitness program recommends. You can’t let them make this decision for you. Always look at the intent, the context, and the content of the proposed solution, making sure that they align with your needs.

There are many choices out there. Sometimes these choices contradict each other. Many of them work in the short term, just because they are simply “better than nothing,” but others have proven to have optimal long-term effects, even if they take time to show results. As you might have guessed, these solutions often get overlooked, because we don’t have the patience to wait for results.

For example, let’s look at what’s being popularized by the mass media and on the Internet: fads like the 10-or-so-minute workouts, month-long or week-long challenges, and the “simple” exercises “everybody must do to fix all their problems.”

These miraculous, sounds-too-good-to-be-true solutions get our attention every time. We love to read these trending articles and to watch quick videos making overreaching promises. They give us hope, and they entertain us. Our views and likes (in the millions) incite content-creators to produce more articles and videos of a similar nature, resulting in thousands of publications bombarding us with the same advice. No wonder we don’t question them; if so many people, publications, and organizations say the same thing, then there must be something to it. As you may discover, however, our likes just dictate what we want to be “fed” – what we already want to believe in. The content-creators are just doing their jobs, giving us what we want. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be reading their magazines or blogs; we wouldn’t be watching their videos and listening to their podcasts. Perhaps we shouldn’t!

Additionally, generic workouts are a lot like pre-made food, immediately ready for consumption, packaged in a box covered all over in big promises. Convenient? Maybe. Yet, nothing beats a fresh, mindfully prepared, and balanced dish full of the nutrients your body needs – and enjoys. Once again, just like with food, you need to know what you “feed” your body in terms of exercise. Therefore, I urge you to educate yourself more on this subject before you commit your time and your health.

How Can Fragmented Exercising Help?

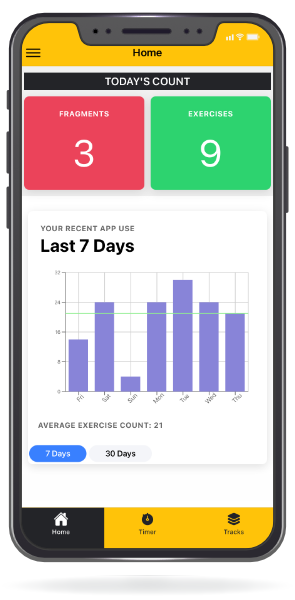

Fragmented exercising (FE) is not composed of a fixed set of exercises. It is a collection of principles – a blueprint, if you will – allowing you to make informed decisions. It will help you create a solution tailored to your personal needs.

I believe that fragmented exercising is the most practical, functional, contextual, and, therefore, most effective approach to personal fitness for people who spend a lot of time sitting, whether at work, school, or even at home. That is the contextual side of FE.

It’s a multidimensional and comprehensive approach, implemented with great consideration for our physiology, and the environmental and social aspects of modern life. This makes it functional, efficient, and effective, but, moreover, fragmented exercising is quite simple to implement. Therefore, it is very practical!

The next chapter is dedicated to one of the most important fundamental concepts you must understand and master if you want to succeed. To make exercising a lasting habit, you need to learn how to enjoy movement again.

Why “again”?

We were born to move. Nature made sure that we enjoyed movement, and enjoyed exploring new ways to move. That’s why fetuses start kicking as early as 18 weeks from conception, while still inside their mothers’ wombs, before they fully develop. This is the manifestation of our first true desire: to explore our surroundings via movement.

As we emerge into the world, we continue developing in response to the environment and our interactions with it. We crawl, we walk, we run, we climb, we jump, we play, we dance. At some point around the time we reach maturity, however, we witness a decline in our internal motivation to move. That is why many struggle to maintain active lifestyles.

We may rely on external factors for motivation, but that motivation won’t last. Your doctor’s recommendations won’t do it for you. Your peers’ opinions or your spouse’s desire to help won’t be enough. The only reliable source of real, limitless motivation is to enjoy the movement for what it is. But is it even possible to reclaim that instinctual craving for movement? You're about to find out.