Strings Attached

John was born into a world of constant gravity. The force that acts upon us from conception until our very last moment on this planet, yet we rarely give it any thought.

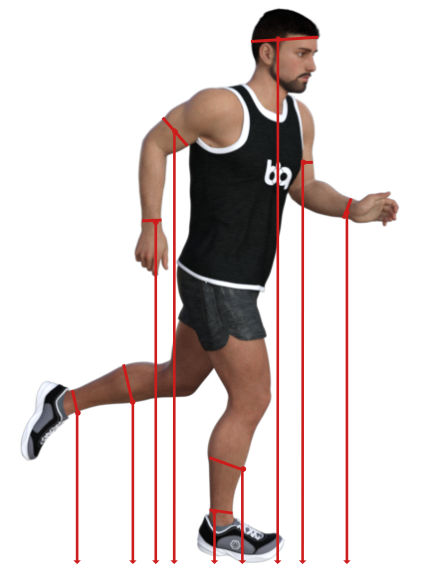

Imagine a set of rubber resistance bands pulling down on every part of your body at all times. While that’s an oversimplified way of looking at it, it should give you a bit of a visual.

A more proper way of looking at it would be imagining a set of who knows how many minuscule rubber bands that pull every cell of your body towards the surface of our planet, because gravity impacts us on all levels, down to the cellular and, possibly, even atomic levels. That, however, is an image that could be quite hard to conceive in one’s imagination – even harder to represent it with a picture. Therefore, we will stick with the original image: a bunch of rubber bands that pull down on every part of the body

And so, John was born into a world of constant gravity. To be able to raise even a finger, he had to defy the resistance imposed by the gravitational force. It took him a while, but his muscles got stronger and he mastered a lot of hand gestures; within a period of a few months, these gestures turned into somewhat meaningful/purposeful actions. His legs followed the same pattern, and, soon, he could imitate a flipped-over bug grasping at the air while trying to get back onto its feet.

John’s next goal was set on lifting his head and learning to hold it up. That turned out to be a challenge that took some time to accomplish because his head was much heavier than any other limb he had mastered to move thus far.

In order to balance his head on the tip of his spine – for example, when his parents started sitting him up – his nervous system had to activate a chain of small stabilizer muscles surrounding all of the vertebrae along the spine, from his atlas bone all the way down to the coccyx. Prior to this, he had mostly been using these muscles for brief contractions to wiggle himself around, but, with this development, he took it to a whole other level.

His spine had become the bridge linking the five separate movable segments of the body – legs, hands, and head (or, rather, the neck). This linkage concluded the formation of one long kinetic chain that became a versatile platform that gave John new opportunities to perform more complex and more useful movements.

By utilizing his newly acquired (yet still quite foreign) contraption of a body, he explored more ways of balancing himself, finding new levers and muscles to play with. It didn’t take him long to assume a crawling position. That wasn’t enough, however, and, in no time, he was able to stand on his feet. The discovery of new ways of movement excited John, and he kept on going, although he had no business to attend to nor any errands to run. I guess he just enjoyed movement for what it was.

Please note, we are all born with an internal desire, a mechanism that excites us when we move. It’s like a “starter fluid” that gets us going. I guess nature figured that, if we move, then we will be able to survive, so it made sure that our attempts at it are rewarded with pleasant stimuli. Maintaining a healthy body – free of psychological alarms and physical restrictions – is key to staying active. If you manage to do so, you will never experience any internal resistance, and being active will be easy, because you will enjoy movement for what it is.

Once John was able to stand upright, he discovered that, if he leaned forward enough to lose his balance and then alternated moving his legs while keeping his torso more-or-less erect, he could move around in space (also known as walking). Little did he know that it took hundreds of muscles working in sync to achieve this. His nervous system – the smart and resourceful orchestrator – took care of that for him.

After just a few years of playful interactions with our planet’s gravitational force, John had become quite proficient with his body, mastering all major movement patterns. Guided by his natural instincts and, of course, gravity, his body figured out the proper form for running, squatting, and doing other essential movements.

John could move efficiently and safely without wasting energy. He achieved proper alignment and acquired great control of his movements, which is crucial for limiting the physical stresses resulting from his interactions with the surrounding environment.

While we’re on the subject of alignment, we must emphasize that John’s postural alignment at this age was rather good – perhaps even perfect. His body had not been subjected to repetitive or excessively hard work; he hadn’t been forced to sit for longer than would feel comfortable to him. Thus far, the only real physical challenge in his life was the Earth’s gravitational pull, and his body had been adjusting to dealing with it quite well.

How to Become the Perfect Self

Let’s pause our story for a moment. I have always been intrigued by the intricate, yet seemingly simple mechanism that allows humans and other animals to become who we are; though there are slight variations in our gene expressions, we are, nevertheless, almost always the nearly perfect versions of ourselves. All it takes is being who we are in the environment in which we are designed to live.

To be the perfect version of yourself you need to be who you are in the environment in which you are designed to live… Nature already gives us – the perfect environment for our perfect existence. We just forget to use it.

Perhaps many of the issues that corrective exercise specialists try to address with elaborate exercise regimens can be reversed and managed with what nature already gives us – the perfect environment for our perfect existence. We just forget to use it.

We go to gyms and use primitive apparatuses that target certain muscles in isolation. We challenge every part of the body separately, forgetting that we had worked so hard at the beginning of our lives to fully utilize this beautiful, versatile system of interconnected pieces. We also forget that, in real-life situations, without restrictions and the safety measures of exercise equipment, we will have to invoke different combinations of muscles to perform actions seemingly similar to those we perform at the gym. As you understand, training your muscles in isolation can be just as ineffective as training each player of a sports team separately, then bringing them out to the court to play together for the first time on game day. It simply won’t work.

Use Gravity

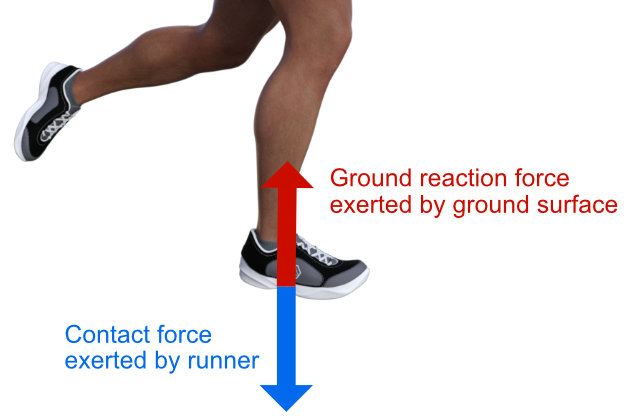

Use the Earth’s gym. Return to basics by incorporating gravitation into your daily routines. As a matter of fact, gravitation may be the main and only real challenge your body was designed to handle. The rest is just a bonus.

NASA scientists that observed astronauts upon their return from space have deducted that gravitational pull is an integral factor in our proper physical development. It is more than just some external force that we deal with at all times; it’s “a signal that tells the body how to act.”* If our genetic code is a blueprint for our body, then gravity is the foundation on which our body is built in accordance with this blueprint. Even a slight interference on our part is likely to impact the integrity of the whole structure. But how can we interfere with gravity? You may think it’s impossible without going to space.

As it turns, we can very well decrease or, at least, distort the effect of gravitational force by engaging in a chronically sedentary lifestyle. Dr. Joan Vernicos, former NASA scientist and the author of Sitting Kills, Moving Heals, compares the effects of spending time being sedentary on Earth to those caused by gravity deprivation among the personnel of orbital space stations. Of course, transformations in the context of the microgravity of space happen much faster than here on Earth, where we can experience only partial gravity deprivation. In the long run, however, it will all come down to a quite similar result, in which our posture, among many other things, will be compromised and it will no longer be feasible for completing even simple everyday activities.

If you jump out of your seat after years of chair-conditioning, you will be, in a way, similar to an astronaut who has just returned back from a space voyage. Your body needs time to acclimate, to get readjusted to new conditions before you can put it to use. Otherwise, you may suffer dire consequences, such as physical traumas.

We started talking about posture for more than just purely aesthetic reasons. Many think of posture as the ability to stand erect, with natural spinal curves. For some reason, we choose to limit our focus to only the spinal curvature when we talk about posture. In reality, posture has no boundaries, nor is it limited to one default position. Posture is a snapshot of your form at any moment of time. It’s dynamic. It’s all-inclusive.

You must think of it as of visual representation of your active kinetic chain, including every part of the body, from the crown of your head all the way to your toes. Assessing your posture means assessing your ability to engage the right segments of the kinetic chain for producing powerful movements with great control and minimal energy exertion while dealing with the strings of gravity attached to each part of your body. Bad posture can be defined as the inability to move efficiently and safely, wasting energy and putting one’s body in danger.

Keep in mind that, when we talk about preserving your posture, we’re talking about preserving your kinetic chain and maintaining its functional integrity, which is the foundation for your active existence on this planet.

* Gravity Hurts (So Good) @ NASA.gov - https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2001/ast02aug_1