Yanking the Chain

When it comes to the body, with great power comes the need for great control. Otherwise, injuries will be unavoidable. Injuries, in turn, will lead to the introduction of temporary or permanent movement compensation patterns, short- and long-term adaptations, and physical and neurological restrictions.

If you want to lead a healthy, active life, then protecting the integrity of your kinetic chain must be your utmost priority. To strategically approach this task, we need to understand how sitting affects our body structurally.

Breaking in Two

First of all, sitting breaks our body into two parts. One (from the hips down) stays inactive most of the day, and the other (the upper body) is overused throughout the day to complete repetitive tasks or strenuous work – for example, the persistent isometric contraction of muscles performed to keep our upper body upright.

When people stop challenging their leg muscles with regular physical activities, the body will start wasting the muscle, just like what happens to the astronauts in space experiencing gravity deprivation. The density of blood vessels in the muscles of the legs and buttocks will also decrease, significantly lowering the amount of blood supplied to the muscle cells, as well as to other tissues and structures of the body, including the joints. As it subjected to partial muscle atrophy and a diminished supply of blood, the lower part of the body will become weaker. The blood-deprived joints will also suffer from an inconsistent nutrient supply, which will affect their physical condition. Without the strong foundation provided by the legs, the rest of the body won’t be able to function optimally either.

It’s worth mentioning here that we are not designed to stay still for hours while keeping our backs upright and balancing our torso on the buttocks. Excluding the lower part of our body (our feet, legs, hips) from the “balancing act” puts more strain on the muscles of the torso. The long kinetic chain throughout which we should evenly distribute the workload now becomes much shorter. Therefore, the muscles that are used to keep our torsos erect will have to work harder.

That’s why our backs get more tired when we sit than when we walk. That is why the lower back may hurt after an hour of sitting, but not after an hour of hiking in the park.

Little by little, our nervous system learns to use the upper part of the body independently from the lower part, especially if we limit the time we spend in physical activities that utilize the whole body. You could say that the upper half of our body has its own independent life. It learns to deal with challenges on its own. Don’t be surprised when, after a few years of chronic sitting, you start feeling clumsy whenever you try to do something that requires the use of your whole body. It can be shocking how unnatural some moves feel, even though we clearly remember ourselves gliding through them on autopilot just a few years prior. Or was it 10 years ago?

We also accumulate pains, stiffness, and inflammations from the constant overuse of muscles and joints thanks to the repetitive tasks that we perform at work – typing, drawing, writing, assembling parts. Our upper body becomes sensitive and fragile.

We no longer see ourselves as the reliable, sturdy, and heavy-duty machines we ought to be if we were to survive in nature. Rather, we see ourselves as brittle statues, standing on shaky pedestals, waiting for an accident to happen.

Think about it! In nature, we would spend many years building this monolithic unity made up of many different parts to ensure that our bodies could become strong, coordinated, and capable of dealing with the various physical challenges that we might face. Now, something as trivial as sitting pulls us tens of years back in our personal physical development, making our bodies as sensitive and as fragile as those of little babies. It’s no wonder that, when we go about our “grown-up” lives, trying to do what we should be able to do, our bodies still break. The same thing would’ve happened to a baby if you made it do things beyond its abilities.

Tension Re-Adjustment

Or the new neutral (New-tral)

We have already discussed how the body and its nervous system have the ability to adapt to demands or physical challenges. Here, we will mention yet another interesting way our body adjusts to sitting.

To make it somewhat visual and simple to understand, let’s imagine that our muscles are metal springs.

If we were to keep a metal spring stretched for a long period of time (days, weeks, or months) and then release it, it may not shrink back all the way to its initial form. Depending on its material composition, it may remain slightly elongated compared to its previous resting shape. If we keep a spring compressed for an extended period of time and then let it go, it also may not entirely return to its initial form. It will appear shorter.

A very similar thing happens to our muscles and connective tissues as we commit ourselves to chronic sitting. Our nervous system will try to pick up the slack of chronically shortened structures and release the tension in chronically stretched structures. Why?

It all has to do with how our nervous system senses internal and external changes. Tension in our muscles gets translated into a signal (stimulus) that is monitored and processed by our nervous system. Among other things, our brain needs this information to figure out our position in space – known as proprioception.

As we know, however, our brain processes all these signals sequentially, one at a time. Apparently, we are not as good at multitasking as we think we are. So, how does our brain deal with all the information that comes its way? To answer in one word: Quickly!

A human brain is capable of carrying out around one thousand trillion logical operations every second. It can’t afford, however, to spend too much of its time on one single thing. Therefore, we are designed not to waste our cognitive resources on what happened some time ago – even if it happened relatively recently, like a few seconds prior. We mostly devote our attention to what’s happening now. In other terms, we sense changes rather than the current static state of things.

You can observe this by putting your hand in hot-ish water. You will feel its warmth for a moment, but then you get used to it. Pull your hand out and now you’ll feel cold at room temperature, but also for just a brief moment.

In other words, if it’s not dangerous, then you don’t really need to do anything about it, so your brain turns off that channel of information. It’s old news for you. If this didn’t happen, then our sensory system would be overwhelmed with a plethora of signals bombarding our brain. In such a case, we wouldn’t be able to respond to these signals appropriately.

But what does this have to do with sitting?

Recall an intercontinental flight or a many-hour drive you’ve taken. As you sit down, your body conforms to the shape of the seat. Your brain momentarily assesses the position of your body in space by getting information from all the sensors measuring tension in muscles and surrounding tissues throughout your body. It also gets information about the pressure in the areas in contact with the seat. If you sit down on a hot or cold seat, that information is sent to the brain, as well.

In just a few moments, once you have readjusted the seat and put on your safety belt, all the initial sensations related to you sitting down will go away. Now, you just concentrate on your trip or whatever else you are doing, but the tension in your muscles, tendons, and ligaments didn’t go away. Your brain, your nervous system just moved on to sensing and processing other information.

But then comes the moment when you finally get out of your seat for the first time in hours. Doesn’t it feel like you can’t straighten out your body right away? Perhaps walking (or even standing) feels kind of funny for a moment, as well. It will take a minute or two for you to get back to your “normal” self.

What happened in just few short hours can be described as tension readjustment (or, rather, readjustment of your reaction to the tension). That sitting position briefly became your new normal (or new neutral) because your body stopped sensing it. As you get up out of the chair, your body will sense the change and reverse the adjustments to yet another “new normal.” Yes, you are right, it doesn’t take long for the body to start optimizing itself for the current task at hand. You can call it a temporary specialization.

Remember, though, that your body is smart (or lazy, depending on how you look at it). If you do something often enough, it will look for a way to adapt to the task on a permanent basis so it doesn’t have to waste resources on readjustments, amongst other things. If it has to constantly ignore the tension in the muscles and connective tissue as we sit for most of the day, it makes sense for the brain to readjust for sitting permanently so there will be little-to-no tension as we sit. So, our regular neutral (or “new”-tral) position starts resembling our sitting position more than anything else.

Yes, just like in the metal springs example, after many years of sitting, some of our muscles may become chronically elongated or shortened because our body has readjusted, adapted. Anything else outside of this “normal” may not feel, well, normal. That's why people whose bodies specialize in sitting don’t get tired of sitting – it just feels right. Other activities that may involve standing upright, however, may feel quite uncomfortable.

When a sedentary person is asked to stand up straight, he or she won’t be able to assume good, optimal posture, although they all may think that their posture is perfect or close to it. The following experiment conducted by NASA can help you visualize this.

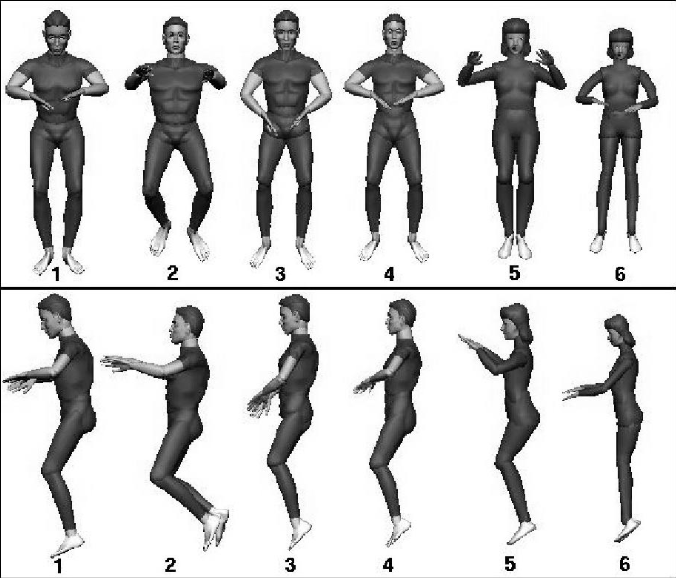

In their attempt to study a natural body position (natural posture), NASA's scientists directed astronauts to assume a comfortable, neutral position while blindfolded with minimal gravity acting on them. This way, they wouldn’t be using their muscles to resist the gravitational pull of the planet and they wouldn’t be inclined to correct their posture according to their visual cues. As they relaxed, their muscles assumed a normal, resting state – just like springs when you let them go.

This is what scientists observed: Every person had a different posture that perhaps reflected their every-day physical activity regimens, old and current traumas, and so on. In spite of their different body positions, they all felt the same way. I bet that, if we showed them a set of pictures displaying different neutral postures and asked them to choose the one that they experienced during the experiment, they all would probably pick the same picture. What we feel and what we are, apparently, can be quite different.

I wish we had such an instrument here on Earth so that we could just see what sitting does to our body, but we don’t, so we rely on our proprioceptive mechanism to tell us whether we’re standing straight. Once our body gets recalibrated to sitting, our neutral/comfortable resting state is skewed towards the sitting position; we will always want to correct our body, even if it tries to do what is right.

This means that we perform our activities with a posture that is far from optimal, even though we think that we move well and with proper form. As we know, that will translate into wasteful and dangerous movement, because we won’t engage our kinetic chain appropriately.

The only way for us to reverse this and make being upright feel more comfortable is to remind our body – through movement – that there’s more to life than sitting.

We can dilute our sedentary days with occasional standing. This is probably one of the cases when I say that you may want to invest into a standing desk. It is noteworthy, however, to emphasize that standing is no replacement for movement. Although being able to stand up once in a while give us a chance for additional variations in our postural expression, going overboard with it will have adverse effects. You must be mindful and careful not to take it to the extreme.

Some find a way to combine a standing desk with a recumbent stationary bike or treadmill to add some activity into their sedentary daily existence. Once again, don’t overdo it. It’s essential to introduce a variety of movements to avoid the overuse of certain parts of your body. Just like your diet, your physical activity needs diversity and balance.