Specialization in Sitting

Being able to sit down and being able to sit for a long period of time are two different skills. You may be able to assume a proper sitting position, but that doesn’t mean you’ll be able to maintain it for an extended period of time, like an hour or more. Think of it as running fast, short sprints versus running paced, long distances races. You can say it’s all just running, but the former requires power and the latter is based on endurance. Usually, you don’t see the same pro athlete running a 100-meter sprint one day and a marathon the next. The reason for this is specialization.

Although athletes participating in either race can be categorized as runners, one of them is specialized in explosively fast short sprints. His muscle fibers are optimized for brief periods of all-out work. His body is not equipped for running long distances. Even if a sprinter wants a challenge and runs a marathon, his results will most likely be far from impressive.

Moving on from the sprinter and long-distance runner, we can look at yet another example related to the leg strength. A powerlifter, who squats extremely heavy weights every other day to keep his legs strong, won’t perform well in a 100-meter run, nor will he find much success in a marathon. Although his legs are objectively strong, his body is specialized in a yet another skill, making him unfit for either of the aforementioned forms of exercise.

If you are still wondering whether it’s a good thing to have a lot of skills, here’s my opinion: as long as your skills don’t conflict with each other (or the trade-offs don’t restrict or endanger you in any way), acquiring more skills should be fine – even advisable.

When it comes to prolonged sitting, however, we find ourselves becoming increasingly specialized in that regard. We practice it so much (perhaps more than anything else) that it becomes deeply embedded in us, even noticeable to the naked eye.

According to the latest census, our life expectancy is around 80 years (roughly 29,200 days). If we consider that an average human spends about 10 hours a day sitting, including driving, studying, working, being at the dinner table or on the couch, watching TV, and plenty of other seat-centric everyday activities, that all adds up to about 292,000 hours. If we believe that, in order to master a skill, one must spend 10,000 hours practicing, this means that we could master sitting almost 30 times in our lifetime. It’s not surprising then that we get quite proficient in it, right? And we do indeed get quite good at it!

We can often spot a dancer simply by the way he or she walks, often with grace and an accentuated upright posture. A powerlifter will display certain traits in his movement, such as, perhaps, a little stiffness. Similarly, we can spot professional sitters just by observing the way they move and even their looks.

Take, for example, the physical attributes of a pro swimmer, such as broad shoulders and a strong torso, or the ballet dancer’s powerful, expressive legs and exceptional posture extending into a long neck. A powerlifter, on the other hand, will have a stockier body with impressive musculature. Of course, neither swimmers nor dancers intentionally aim for the looks and body types they possess. Their appearances are expressions of many adaptations to various stimuli that have been imposed on their bodies for years. As the expression “form follows function” suggests, we can see that their bodies have been optimized to perform certain tasks. In the same way, so has the body of a sedentary person, whether they are an office professional, a student, or anyone else prone to long bouts of sitting.

Do you want to try to list some of the common physical traits of chronic sitters?

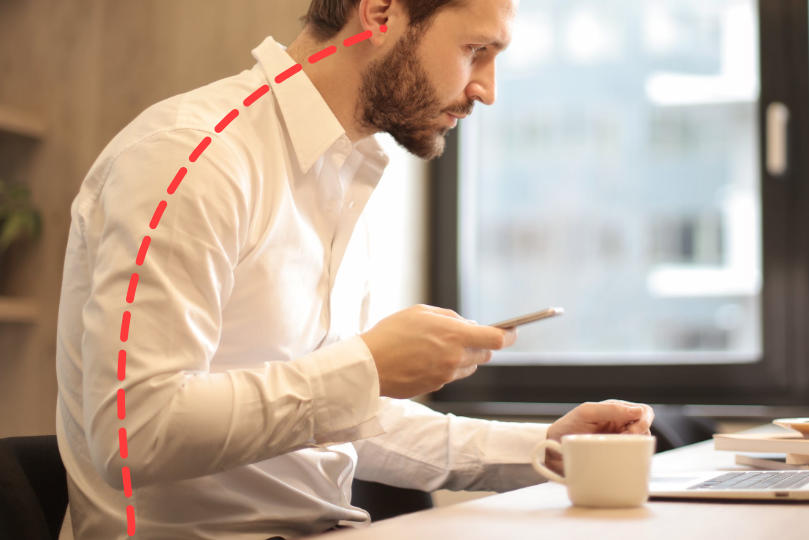

Rounded shoulders atop a slouching upper back, a forward-displaced head, and a flat or over-arched lower back are just few of the things that are immediately obvious to an untrained observer; even a person without any experience in postural assessments can see it as plain as day.

If we were to look closer, there would be many other small – or, in some cases, major – accompanying deviations found along the kinetic chain. If an expert examines a sedentary individual, he would be able to spot quite a few misalignments, muscle imbalances, and other structural and functional issues dispersed all over the body from head to toe. These visible and sometimes hidden attributes are the result of the body’s many adaptations to chronic prolonged sitting – adaptations that we will discuss in details in the upcoming section.

For now, I want you to understand that acquiring the skill of being able to sit for a long time contributes to certain restrictions in the ways we move. Becoming “very good at sitting” – by which I mean being able to sit for long uninterrupted periods - can make our bodies inapt for movement in general. Yes, this type of specialization is due to significant physical adaptations accumulating over the course of many years. These changes affect many structures, organs, and tissues, impacting the way they interact with each other and putting us at risk of hurting ourselves if we try to introduce physical activities beyond sitting. As a matter of fact, if you start working out without adequately assessing, rehabilitating, and preparing of the body for physical exercise, you can injure yourself – even doing such seemingly light activities as brisk walking or riding a bicycle. Such injuries will, in turn, will render you immobile temporarily or, possibly, in the long term. This will defeat the purpose of starting to work out. As a consequence, you may find yourself trapped within a vicious cycle of traumas and immobility, which will inevitably lead to you giving up on the idea of exercising – or even moving beyond just your basic needs.

It is essential for everyone, especially those starting long sedentary careers, to know how to recognize, reverse, and prevent common sitting-induced adaptations. And, as you are about to find out, it’s not as complicated as it may seem.